Participants

The project involved 11 student participants from Garrthalala Homelands School from the Transition to Year 9 class. The project also included strong cooperation from the teachers of the school, Lombinga Mununggurr and Taylor McCormack and the assistant teacher Ganydjira Mununggurr. There were also some members of the Garrthalala community who willingly chose to participate in the project. Verbal and written consent was received from all participants.

Commencement of the Project

From the commencement of the project, there was ongoing communication and planning with the teachers prior to the on-site work. Ideas were shared for the filmed storytelling process as well as discussions with students about possible stories they would like to share. We prepared resources to scaffold and support the students during the filming process. These included storyboards to support students with the process for storytelling as well as visuals to assist students in thinking of what they’d like to share. Prior to the onsite work, we hired the filming equipment in preparation to begin the 4 day on-site project work at Garrthalala Homelands School.

Day 1

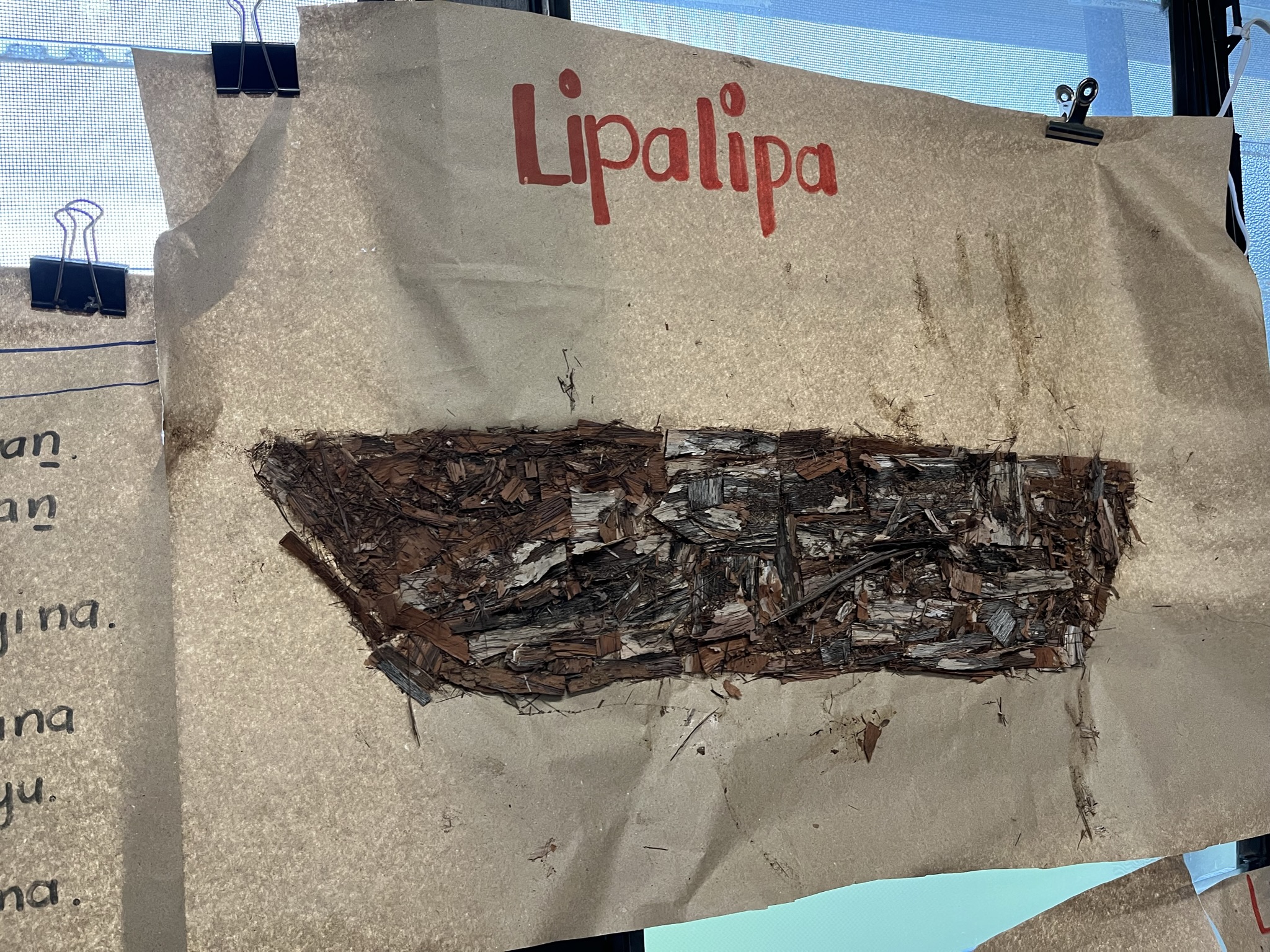

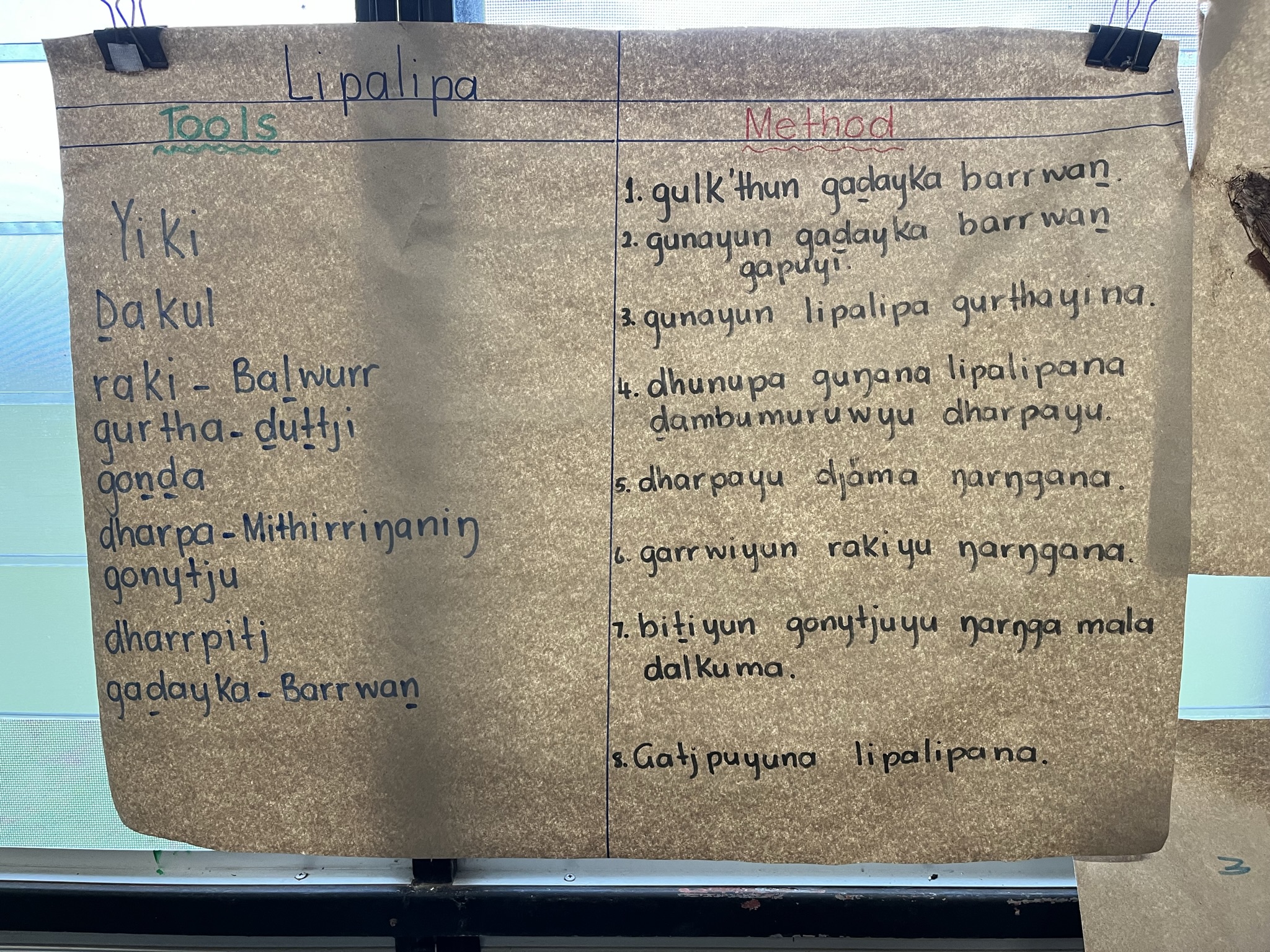

Upon arriving at Garrthalala Homelands School, we were introduced to all the students, in which we were able to meet them and understand their interests, as well as establish a rapport. We discussed and shared story ideas with the students. It was a very exciting process as we got an insight into the different ideas students had to share. Students then decided that they would like to tell the Lipalipa canoe story.

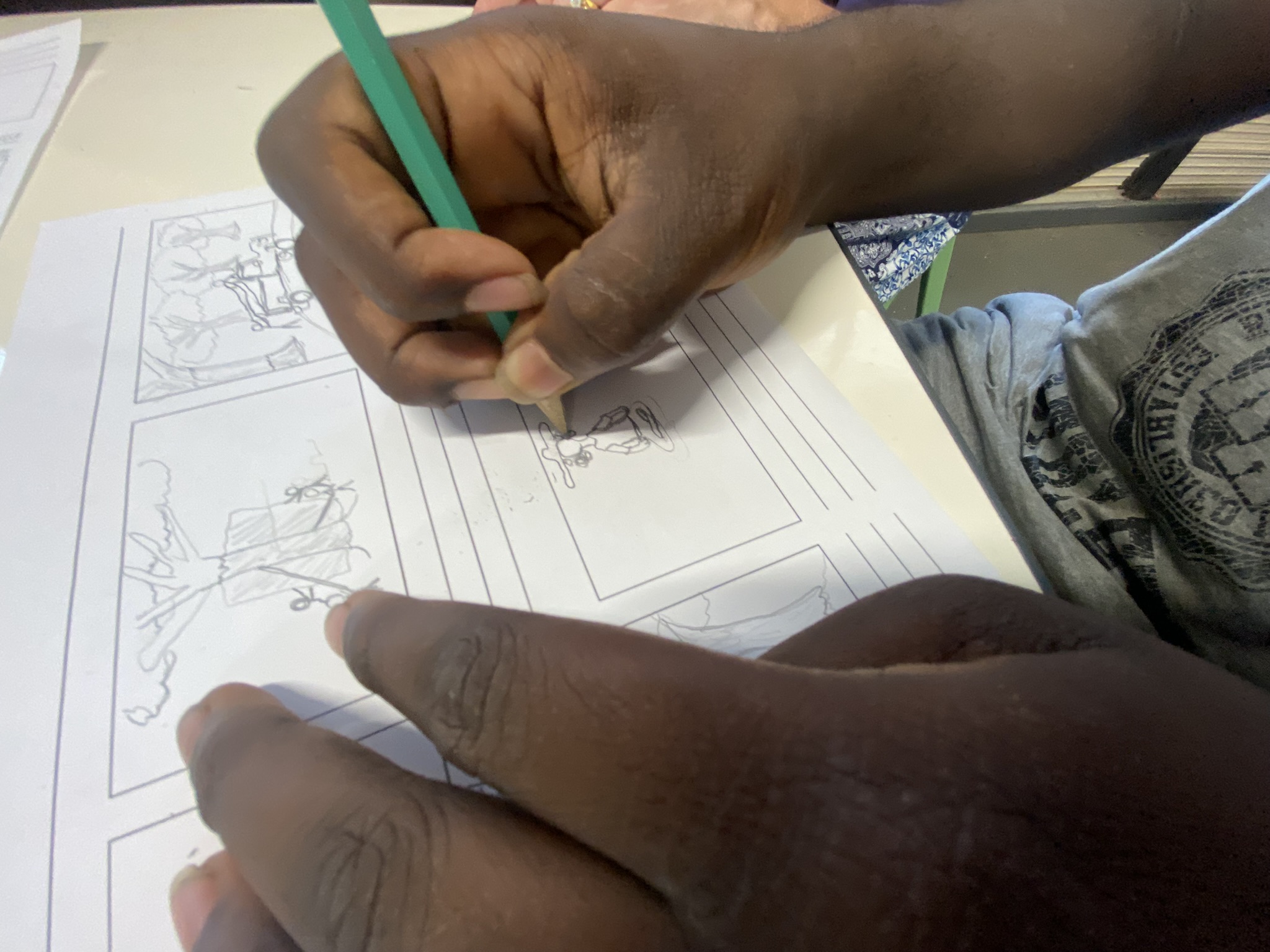

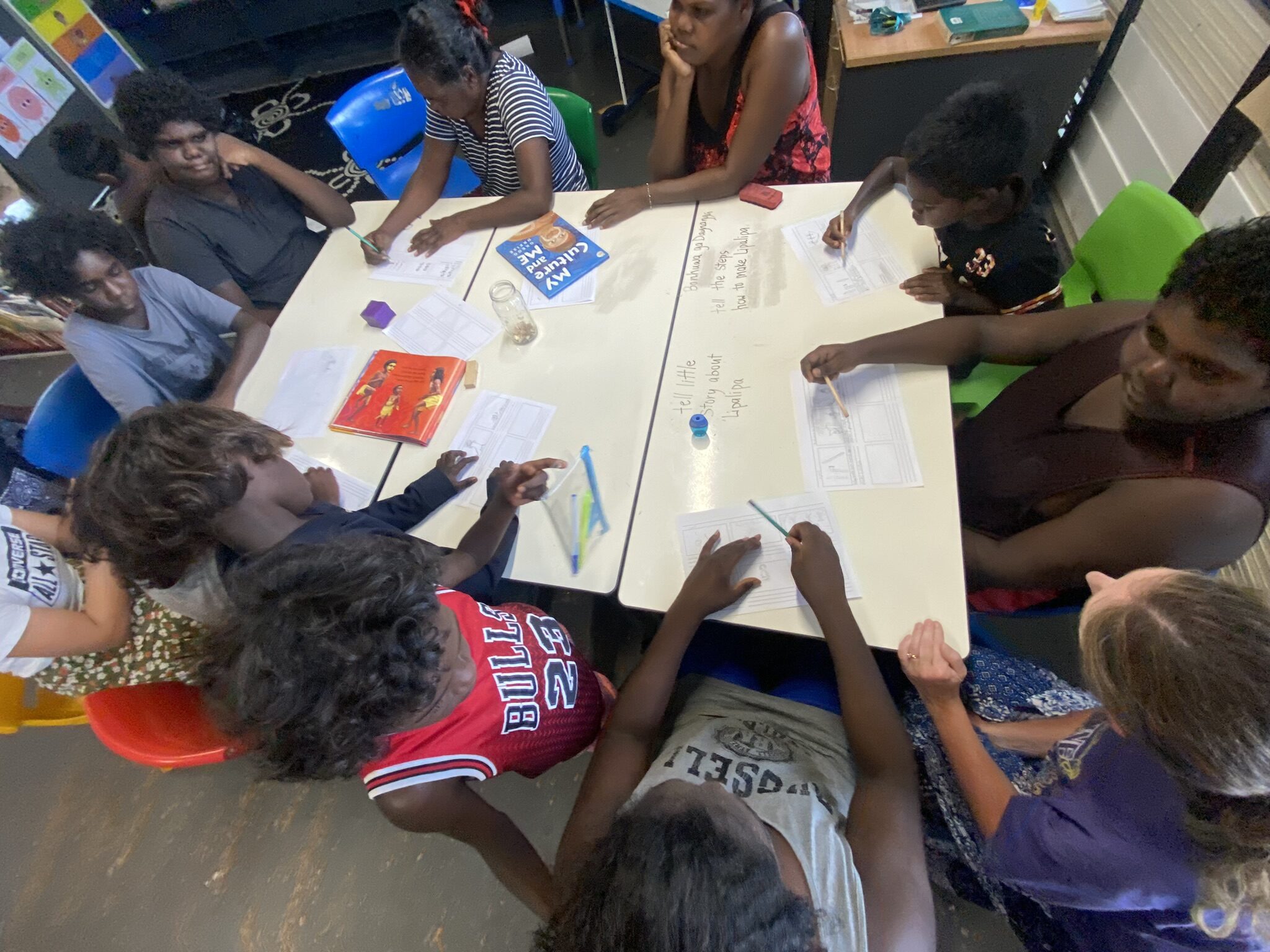

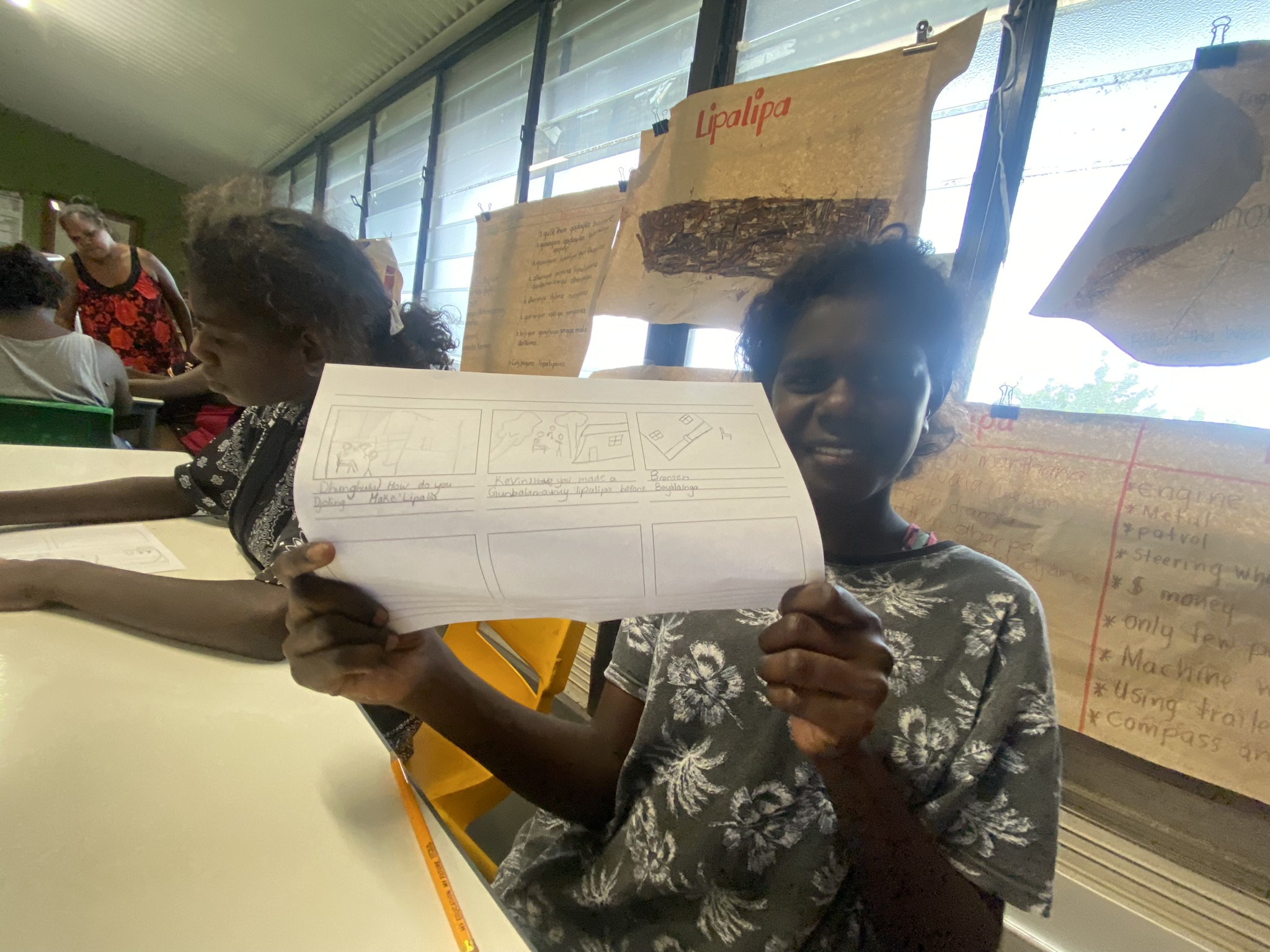

We introduced the storyboarding process in which students were to include the sequence of the story, what the story is about, who is in it and what filming equipment will be used. Visual materials were provided to students to help support those who needed ideas or those who wanted to expand on their ideas.

From there, we formed three production teams. The first team focused on how to make a Lipalipa canoe. The second team focused on interviewing the community members about the Lipalipa story and song while the third team focused on the Lipalipa dance. Within these teams, each student had a key role in their group. They also helped each other at each stage of the project. Finally, all students learned how to use the filming equipment. They were all very eager to get started!

Day 2

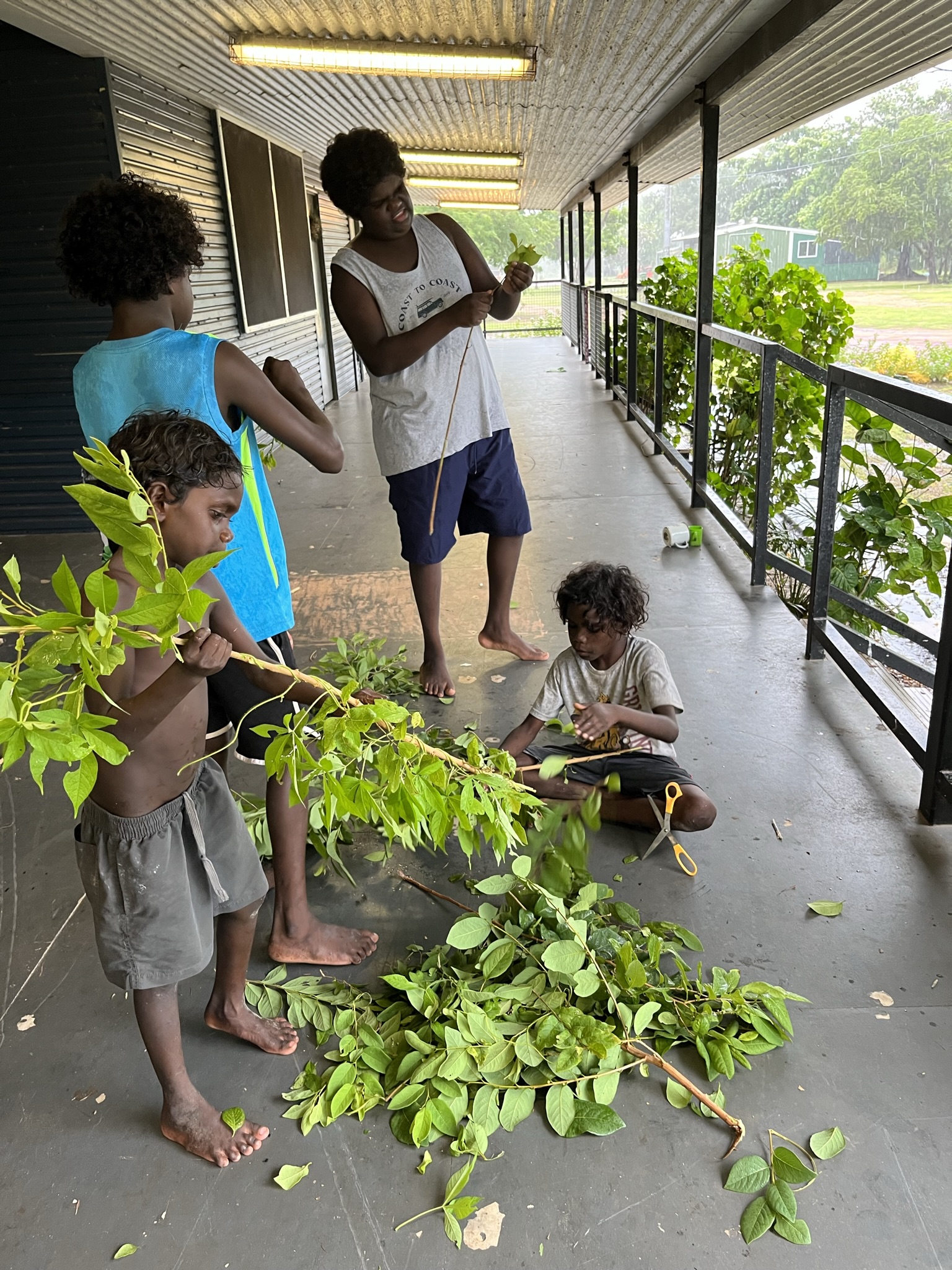

The filming officially began. On day 2, students began filming out in the bush taking the materials to make a Lipalipa. This included removing bark from a tree with an axe. Students then began making Lipalipa. Some students also made clay today, ready to be used the next day for face and body paint for performing the Lipalipa dance. Students also started collecting and preparing sticks from the bush so that they could be used within the dance. On this day, students also rehearsed the dance!

Day 3

By day 3, the project was well underway. One of the production teams began filming the interview with two community members. One interview was about the Lipalipa story while the other interview was about the Lipalipa song.

Filming included recording the singing of the Lipalipa song with clap sticks and accompanied by didgeridoo playing.

Students also began painting the clay on their face and body. They performed and recorded the Lipalipa dance. It was fantastic!

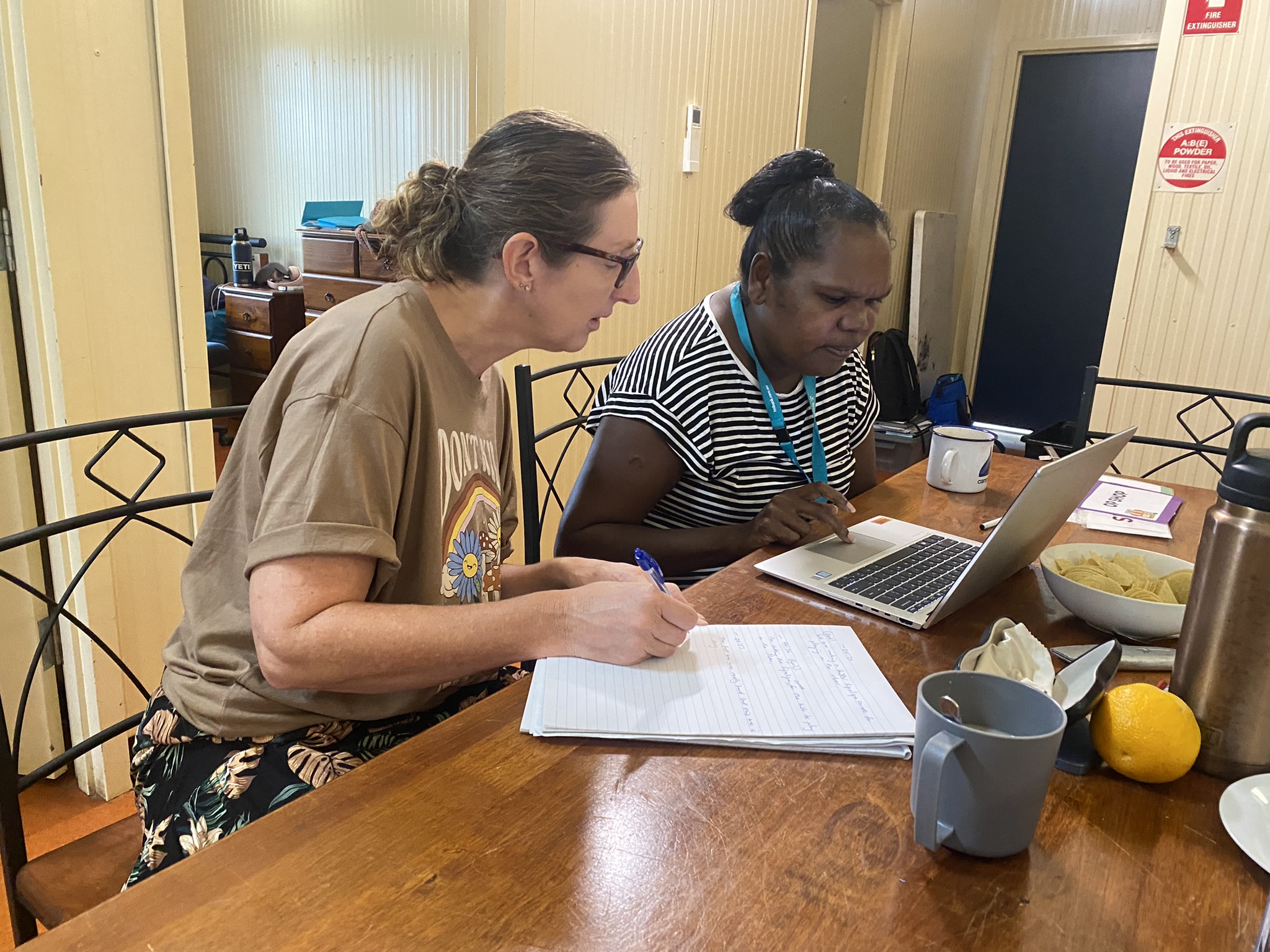

With the assistance from the Indigenous teacher and assistant teacher, we started translating and transcribing key aspects of the film’s storyline; from Yolngu Matha to English.

Day 4

Day 4 was our last day onsite for the project. We finished translating and transcribing key aspects of the film story line from Yolngu Matha to English with the support from the Indigenous teacher and assistant teacher.

Throughout the process of the project in Garrthalala, a translanguaging approach was used whereby students and teachers used language according to their needs, purpose, and audience. The students moved between Yolngu Matha and English at various times to discuss their ideas for the story, to plan the story stages, and to communicate with others and their choice of language reflected who they were communicating with.

The language used throughout the film was Yolngu Matha as this is the language of the community and the students’ home language and strongest language, as well as the language that is tied to the culture and the stories. Therefore, it made sense that the film would be in Yolngu Matha. Subtitles have been created in both English and Japanese to expand the reach of the story beyond the Garrthalala community whilst still providing the authentic experience of hearing Yolngu Matha for the audience.

Post Production Work

After completing the on-site filmed storytelling process, it was time to edit the film. The Kochi University (Japanese, English major) students translated the Garrthalala film from English to Japanese for the purpose of creating film subtitles.

The films and the project website were then shared between Garrthalala Australia and Kochi Japan.

Garrthalala Context

What a journey to Garrthalala. We flew from Melbourne to Cairns and then onto Gove where we had a short drive to the town of Nhulunbuy. Due to being the wet season there were concerns about whether the small planes would be able to fly in and out of the Homelands communities in the wet weather, so it was therefore decided that we’d travel out to Garrthalala from Nhulunbuy by 4WD.

It was a 2 ½ hour journey on very bumpy, muddy and rough dirt roads. Getting bogged twice in the mud and needing to be winched out by a local ranger who is a member of the Garrthalala community provides some insight into the level of difficulty in travel, particularly during the wet season, and to the remoteness of the location. The wallabies and dingoes we saw along the way added to that.

At the end of our long journey, the bushy dirt road we’d been travelling along suddenly opened up to a large, cleared dirt area and there was a sign telling us to look out for planes. We carefully crossed the runway and approached Garrthalala Homelands.

The community is situated along the beautiful coastline of North-East Arnhem land and was better than any film setting we could imagine. We had arrived in heaven and were ready to embrace the community, language and culture and engage in the project. We were however, on the lookout for crocs, snakes and wild buffalo that we didn’t want to be part of our project.

Practitioner Reflections

What a privilege it was to be invited to the Garrthalala community and to work with the teachers and students on the Community Banashi filmed storytelling project. We were overwhelmed by the warm welcome we received and the level of enthusiasm and engagement by all involved.

The bilingual classroom environment was an impressive space where students’ home language, Yolngu Matha, was a key driver of students’ learning and was paired with the authentic use of English. These languages were modelled by the classroom teachers that included a Garrthalala indigenous teacher, a fly-in fly-out teacher, and a Garrthalala indigenous assistant teacher. The way these three teachers worked together to create the learning environment and language environment for the students needed to be seen to be believed. There were 11 children in the Transition to Year 9 class, comprising many siblings and cousins. This provided cross-age, multi-level learning. It was within this context that our project took place.

One of the greatest things that stood out during this project was the layers of story upon story we were uncovering. Early on we knew that the filmed storytelling was about the Lipalipa canoe, but very quickly we realised that there were stories, knowledge, cultural practices and traditions behind each aspect of the overarching story of Lipalipa. There was a Lipalipa song that one member of the community was the leader of, there were protocols about who could perform the Lipalipa dance, their role in the dance and their position in it. The cultural practice of making clay and reasons behind the colour of clay that could be used for each purpose was also embedded in tradition and stories. Each of these learnings for us enhanced the experience of working with this community and added to the level of insight that we gleaned from the filmed storytelling project.

As we said good-bye on our last day, we knew that we were so fortunate to have had the experience we did. We had the tiniest insight into this language, culture and community and despite being such a small insight, it was extremely impactful. We hope that others watching the film will enjoy it and also get a sense of the strong culture, traditions and language that encompass it.